By Squirrel for Mayor

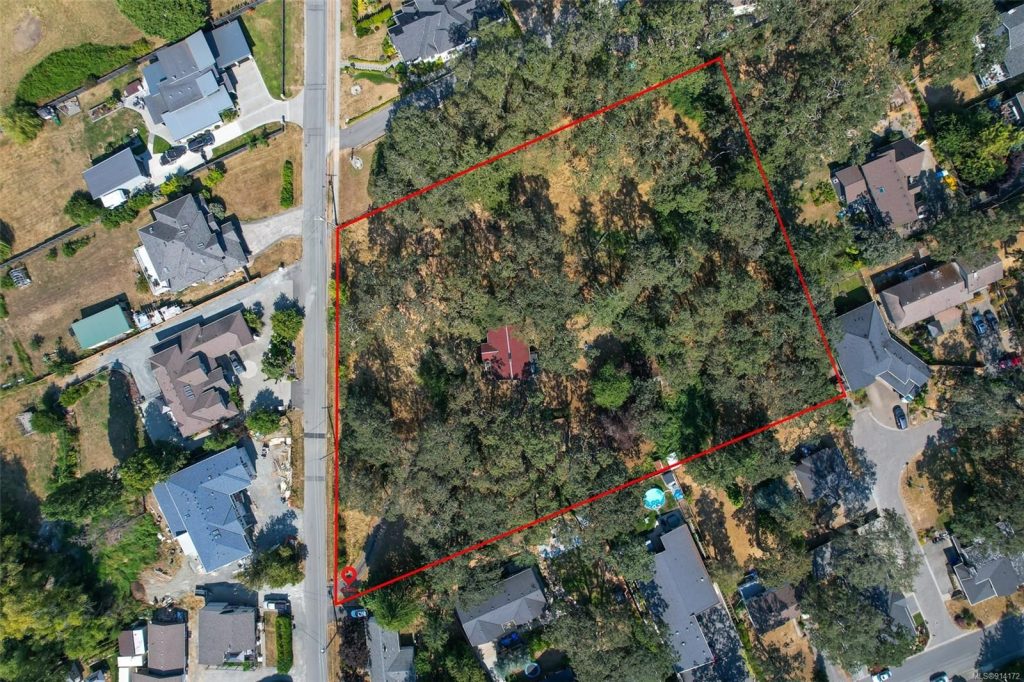

In spring 2025, a piece of land in Saanich, BC—two acres of former hobby farm at 4015 Braefoot Rd.—became the flashpoint for a wider conflict. A rezoning application proposing 24 townhomes quickly sparked a contentious divide between those focused on increasing housing supply and those alarmed at the ecological cost. But this controversy isn’t merely about houses versus trees—it’s about how we talk about growth, what we value, and what narratives we allow to shape public decisions.

Much of this early response has unfolded in local online forums, including a widely shared community discussion thread that became a focal point for public reaction well before the proposal reached Saanich Council.

The proposal has not even come to Saanich Council yet, and it has already ignited online, where a single community post in February 2026 generated more than 500 reactions and over 450 comments. The scale of the response underscores that this is not a fringe issue, but a flashpoint touching deep anxieties about housing, growth, and what is being lost in the process.

A Rare Ecosystem Framed as an Obstacle

The Braefoot site is not vacant land. It supports a functioning Garry oak meadow and woodland, including approximately 120 mature Garry oak trees, more than half of which are proposed for removal. Garry oak ecosystems are among the most endangered in Canada. Garry oak trees are slow to regenerate, highly specific to place, and support hundreds of co-evolved plant and animal species.

Yet much of the public conversation treats the site as interchangeable—just another parcel awaiting “better use.” Ecological complexity is reduced to a tree count or a mitigation strategy, as though mature ecosystems can be offset elsewhere through landscaping or replacement planting.

What disappears in this framing is ecological time. A newly planted tree does not replace a centuries-old oak embedded in living soil, fungal networks, and species relationships that take generations to form—if they can form again at all.

Deep Time and Agroecological Management

The Garry oak ecosystem is not a recent or accidental landscape. Garry oak trees emerged following the last glacial retreat roughly 8,000–10,000 years ago and was actively shaped through Indigenous agroecological management for millennia. For lək̓ʷəŋən and W̱SÁNEĆ peoples, Garry oak meadows were tended landscapes—maintained through practices such as controlled burning, selective harvesting, and seasonal movement that sustained open meadow conditions, enriched soils, and supported complex food systems. These practices fostered biodiversity rather than diminishing it, producing the open-canopy woodlands and species-rich understories that persist today. The presence of mature Garry oaks at sites like Braefoot is therefore not incidental; it reflects long-term stewardship and ecological continuity. When such landscapes are treated as vacant or underutilized land, this deep history of care and co-evolution is erased, and with it the understanding that these ecosystems cannot simply be recreated once removed.

“They’re Just Trees”: Language That Diminishes

Public commentary around the proposal reveals how easily ecological value is minimized. Anonymous but representative remarks illustrate a pattern:

“They’re just trees — we can plant new ones somewhere else.”

“We can’t keep stopping housing for a few old oaks.”

“It’s not even a real forest, just scrubland.”

“Housing matters more than some meadow.”

These statements are often framed as pragmatic or compassionate. Yet together, they rest on a shared assumption: that ecosystems are interchangeable, replaceable, and secondary to human needs.

This language does real work. By flattening the Garry oak meadow into generic “green space,” it becomes easier to justify its removal. The site is no longer understood as a functioning ecological system, but as an inconvenience—something sentimental people are irrationally attached to.

At times, ecological concern is dismissed outright as obstructionist or bad faith—often summarized, inaccurately, as NIMBYism. Used this way, the term avoids engagement with the actual substance of what is being raised.

Climate Resilience and the Role of Garry Oak Ecosystems

Garry oak ecosystems are also critical to climate resilience in a rapidly warming region. Mature Garry oaks are exceptionally drought-tolerant, deep-rooted, and long-lived, making them far more resilient to heat waves, summer water scarcity, and extreme weather than most replacement plantings. Their open canopies moderate ground temperatures, reduce urban heat-island effects, and support soil systems that absorb and slowly release water, helping to mitigate both drought stress and stormwater runoff. Unlike young or ornamental trees, mature Garry oaks store carbon over centuries and maintain ecological function through climatic variability rather than collapsing under it. As climate impacts intensify, removing intact Garry oak ecosystems in favour of short-term development undermines the very resilience strategies municipalities claim to prioritize—trading stable, climate-adapted systems for landscapes that will require ongoing intervention to survive.

The False Choice Driving the Debate

What is consistently erased is nuance. Many residents concerned about Braefoot have long supported missing-middle housing, infill, and density. The issue is not whether housing should be built, but whether this particular site—a rare, functioning Garry oak ecosystem—is an appropriate place to absorb that pressure.

By framing the debate as housing versus nature, public discourse sidesteps harder planning questions:

- How can housing be added with the least ecological cost?

- Which ecosystems are irreplaceable once lost?

- How do we plan for long-term resilience rather than short-term targets?

The urgency of housing is real. But urgency does not justify erasing ecological reality.

Equity, Canopy, and a Misapplied Argument

Equity-deserving neighbourhoods across the region need more urban canopy, cooling, and access to nature. That goal is widely supported—and necessary in a warming climate.

But increasing canopy equity does not require reducing ecological equity.

Garry oak trees are not surplus canopy. They are keystone trees that support hundreds of species—birds, insects, mammals, amphibians, and plants—that cannot survive without them. Removing intact, or modified ecosystems under the banner of equity misunderstands the concept entirely.

Equity is not achieved by trading one species’ livability for another’s, nor by sacrificing rare ecosystems to compensate for historic planning failures. True equity requires both restoring canopy in under-served areas and protecting remaining ecosystems capable of sustaining biodiversity at scale.

OCP Language and Policy Gaps: An Index

The controversy at Braefoot also exposes gaps between stated policy intentions and on-the-ground outcomes, many of which have been documented through ongoing Garry oak ecosystem research and mapping.

Key gaps include:

- Tree protection tied to building envelopes

Mature Garry oaks may be protected in principle, but become removable once placed within development envelopes or servicing zones—creating a loophole rather than a safeguard. - Ecosystems treated as individual assets

Policy language frequently focuses on individual trees rather than ecosystem function, overlooking soils, understory species, and habitat connectivity. - Lack of cumulative-impact accounting

Each tree removal is assessed in isolation, even as Garry oak ecosystems continue to decline incrementally across the region. - Outdated or infrequent canopy and ecosystem mapping

Without regular, high-resolution updates, planning decisions rely on incomplete ecological data. - Mitigation language that assumes replaceability

Replanting ratios and off-site compensation are treated as sufficient, despite clear evidence that mature ecosystems cannot be functionally replaced within meaningful timeframes.

These gaps allow development to proceed in technical compliance while still producing significant ecological loss.

What This Framing Costs Us

When ecosystems are framed as obstacles, their removal becomes easier to rationalize. When ecological concern is dismissed as obstruction, planning conversations narrow. And when Garry oak trees and modified meadows on private lands are reduced to scrubland or landscaping, the loss of deep ecological time becomes invisible.

Garry oak ecosystems persist today in part because of Indigenous stewardship practices that shaped and maintained them over millennia. Their survival is not accidental. Their loss is not neutral.

The controversy at 4015 Braefoot Rd. is therefore not just about one rezoning application. It is about how language shapes outcomes—and how easily living systems can be rendered disposable when they complicate dominant growth narratives.

What is at stake is whether communities can hold housing need and ecological responsibility in the same frame, rather than allowing one to be used to rhetorically erase the other.

Garry oak trees and modified ecosystems are not a luxury. They are ecological infrastructure. When housing debates erase that reality, the cost is borne not only by trees, but by the many species—and future communities—that depend on them.

Related Coverage: 4015 Braefoot Rd.

Victoria News — Letter: Saanich development would take a toll on Garry oaks

https://vicnews.com/2025/03/08/letter-saanich-development-would-take-a-toll-on-garry-oaks/

Victoria News — Saanich resident looks to halt transformation of Garry oak meadow to townhouses

https://vicnews.com/2025/04/24/saanich-resident-looks-to-halt-transformation-of-garry-oak-meadow-to-townhouses/

Community discussion thread — Public response to the proposed 4015 Braefoot Rd. development

https://www.facebook.com/groups/1037995487859099/posts/1222081049450541/